|

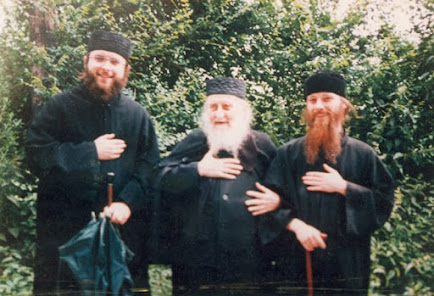

| Saint Sophrony with Father "Nikolai"(left) and "Seraphim". |

The

centrality of the theme in Fr Sophrony is partly determined by the amount of

attention the topic had recently been given by modern thinkers, not least by

Russian theologians and philosophers. The Russian philosophy of personhood

culminates in Berdyaev’s thought. In the theological milieu it was largely Florensky,

Bulgakov, and Lossky who brought the theme to the forefront of debate. Their

trinitarian perspective of personhood contributed significantly to a revival of

interest in trinitarian theology both in the east and in the west. In the

preceding years, as Kallistos Ware rightly observes (along with K. Rahner), the

relevance of trinitarian teaching in Christian theology was largely overlooked.

A

significant reestimation of the issue of personal identity in theology is also

due to the impact of research in psychology. Freud and Jung enhanced the

interest in the inner processes of self-awareness.

Fr

Sophrony’s personal experience allowed him to build up his own understanding of

the concept.

One

cannot easily discover a clear definition within the eastern patristic

tradition of hypostasis that would serve as a determinative background for Fr

Sophrony’s understanding of the concept of a person. Indeed, there is no

clearly definable consensus among the fathers. As Ware observes: “There is in

the Greek Fathers no single, systematic theory of personhood, or even agreed

terminology, but only a series of overlapping approaches.” Neither the dogmatic

legacy of the ecumenical councils nor the Palamite councils and synods offer

any sufficiently full definition of hypostasis. Concerning the church

teaching on the constitution of man, John Meyendorff observes: “There is no

dogma in physiology.”

In

Fr Sophrony also, though the hypostatic principle determines his theology to

the largest extent, there is, nevertheless, no full description of the

hypostatic principle and its meaning, not even in the chapter dedicated to that

theme. However, we may usefully examine some of Fr Sophrony’s allusions to his

understanding of person . He uses the Latin term persona as the equivalent and

synonym of the Greek patristic term hypostasis . In his writings he seems to

overlook the difference between the Greek term hypostasis and the Latin persona,

which is based on an important difference between objective and subjective

overtones.

He

admits how vast is the scope of interpretation of the term hypostasis, even in

scripture: “[it] conveys actuality . . . In many instances it was

used as synonym for essence . . . In the Second Epistle to the

Corinthians (2 Cor 11:17) hypostasis denotes sober reality and is translated

into English as confidence or assurance .” It also denotes the person of the

Father (Heb 1:3), substance (Heb 2:1) and very being (Heb 1:3). All these

various aspects stress, as Fr Sophrony observes “the cardinal importance of the

personal dimension in being.”

Besides

scripture, Fr Sophrony’s approach also reflects his traditional heritage. In

tradition hypostasis emerges out of the distinction between two different

aspects of being (the general and the particular): these were expressed in

Aristotelian terms as prote ousia (prime substance) and deutera ousia

(secondary substance). In the Cappadocians, who articulated the distinction

between hypostasis and essence in the Godhead, hypostasis corresponds to prote

ousia . Fr Sophrony expresses the classical patristic “dualism” in his own

vocabulary: “The hypostasis is a ‘pole,’ a ‘moment’ of the One and Simple

Being, where essence is another ‘moment.’” However, this dualism is

enriched and qualified by the Palamite conception of the divine being, which

elaborates a clear distinction between hypostasis , essence, and energies . Fr

Sophrony, however, prefers to focus on personeity in the Godhead and asserts

the hypostatic principle as the basis of divine being:

The

principle of the Persona in God is not an abstract conception but essential

reality possessing its own Nature and Energy of life. The Essence is not of

primary or even pre-eminent importance in defining the Persons-Hypostases in

their reciprocal relations. Divine Being contains nothing that could be

extraneous to the hypostatic principle.

Thus,

in the Trinity, hypostasis subsumes other aspects of being under its principle:

it determines divine being. The revelation i am that i am (I am Being) shows

that the hypostatic dimension in the Godhead has a prime significance. John

Zizioulas continues Fr Sophrony’s argument on the basis of cosmological

considerations. He rightly observes that creation was brought into being ex

nihilo by someone —a particular (personal) being—O on . The biblical revelation

does not focus on divine essence, placing primary stress on personeity in God,

while in other cosmogonies, be they “Phoenician” (where cosmogony is identical

with theogony) or “Greek” (with its dualism of Demiourgos -hyle ,

Creator-matter), “the particular [personal] is never the ontologically primary

cause of being.” Hence, Fr

Sophrony defines persona as “the one, who really lives.” It is a pivot, an axis

of all being: outside this living principle there can be nothing.

Fr

Sophrony, having established the prime significance of persona in being, does

not proceed to further definitions. As the principle, determinative to all

other aspects of being, persona is not subject to any determination nor, hence,

to any other definition. Even the human persona escapes definition, and remains

“hidden”: “In man, the image of the hypostatic God, the principle of persona is

the very ‘hidden man of the heart’ (1 Pet 3:4) . . . It is also

beyond definition.” Neither is it subject to any rational explanation:

“Scientific and philosophical cognition can be expressed in concepts and

definitions: but person is being, not subject to philosophical or scientific

forms of cognition. Like God, the persona -hypostasis cannot be throughly known

from outside unless he reveals himself to another person.”

Reference:

I LOVE

therefore I A M, The Theological Legacy of Archimandrite Sophrony .Nicholas V.

Sakharov.2002.